Species is First Find of Its Kind in More Than Three Decades

Observed in the wild, tucked away in museum collections, and even exhibited in zoos, there is one mysterious creature that has been a victim of mistaken identity for more than 100 years.

Dr Roland Kays shares the olinguito discovery in a press conference at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences

A team of scientists – including Roland Kays of North Carolina State University and the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences – uncovered overlooked museum specimens of this remarkable animal.Their investigation eventually took them on a journey from museum cabinets in Chicago to cloud forests in South America to genetics labs in Washington, D.C.

The result: the olinguito (Bassaricyon neblina) ―the first carnivore species to be discovered in the Western Hemisphere in 35 years.

The team’s discovery is published in the Aug. 15 issue of the journal ZooKeys.

The olinguito (oh-lin-GHEE-toe) looks like a cross between a house cat and a teddy bear. It is actually the latest scientifically documented member of the family Procyonidae, which it shares with raccoons, coatis, kinkajous and olingos. (Olinguito means “little olingo.”)

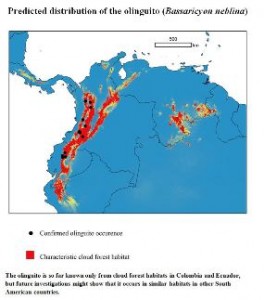

The 2-pound olinguito, with its large eyes and woolly orange-brown fur, is native to the cloud forests of Colombia and Ecuador, as its scientific name, “neblina” (Spanish for “fog”), hints. In addition to being the latest described member of its family, another distinction the olinguito holds is that it is the newest species in the order Carnivora ―an incredibly rare discovery in the 21st century.

“The discovery of the olinguito shows us that the world is not yet completely explored, its most basic secrets not yet revealed,” said Kristofer Helgen, curator of mammals at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History and leader of the team reporting the new discovery. “If new carnivores can still be found, what other surprises await us? So many of the world’s species are not yet known to science. Documenting them is the first step toward understanding the full richness and diversity of life on Earth.”

“The discovery of the olinguito shows us that the world is not yet completely explored, its most basic secrets not yet revealed,” said Kristofer Helgen, curator of mammals at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History and leader of the team reporting the new discovery. “If new carnivores can still be found, what other surprises await us? So many of the world’s species are not yet known to science. Documenting them is the first step toward understanding the full richness and diversity of life on Earth.”

Discovering a new species of carnivore, however, does not happen overnight. This one took a decade, and was not the project’s original goal ―completing the first comprehensive study of olingos, several species of tree-living carnivores in the genus Bassaricyon, was. Helgen’s team wanted to understand how many olingo species should be recognized and how these species are distributed ―issues that had long been unclear to scientists. Unexpectedly, the team’s close examination of more than 95 percent of the world’s olingo specimens in museums, along with new DNA testing and the review of historic field data, revealed existence of the olinguito, a previously undescribed species.

The first clue came from the olinguito’s teeth and skull, which were smaller and differently shaped than those of olingos. Examining museum skins revealed that this new species was also smaller overall with a longer and denser coat; field records showed that it occurred in a unique area of the northern Andes Mountains at 5,000 to 9,000 feet above sea level―elevations much higher than the known species of olingo. This information, however, was coming from overlooked olinguito specimens collected in the early 20th century.

The question Helgen and his team wanted to answer next was: Does the olinguito still exist in the wild?

To answer that question, Helgen called on Roland Kays, director of the Biodiversity Lab at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences and a professor in the College of Natural Resources at North Carolina State University, to help organize a field expedition.

“The data from the old specimens gave us an idea of where to look, but it still seemed like a shot in the dark,” Kays said. “But these Andean forests are so amazing that even if we didn’t find the animal we were looking for, I knew our team would discover something cool along the way.”

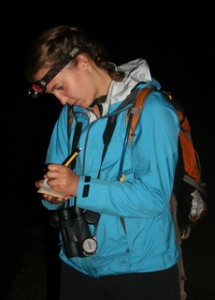

The team had a lucky break that started with a camcorder video. With confirmation of the olinguito’s existence via a few seconds of grainy video shot by their colleague Miguel Pinto, a zoologist in Ecuador, Helgen and Kays set off on a three-week expedition to find the animal themselves. Working with Pinto, they found olinguitos in a forest on the western slopes of the Andes, and spent their days documenting what they could about the animal – its characteristics and its forest home. Because the olinguito was new to science, it was imperative for the scientists to record every aspect of the animal. They learned that the olinguito is mostly active at night, is mainly a fruit eater, rarely comes out of the trees and has one baby at a time.

In addition to body features and behavior, the team made special note of the olinguito’s cloud forest Andean habitat, which is under heavy pressure from human development. Computerized mapping of museum records allowed the team to estimate that 42 percent of olinguito habitat likely has already been converted to agriculture or urban areas.

“The cloud forests of the Andes are a world unto themselves, filled with many species found nowhere else, many of them threatened or endangered,” Helgen said. “We hope that the olinguito can serve as an ambassador species for the cloud forests of Ecuador and Colombia, to bring the world’s attention to these critical habitats.”

While the olinguito is new to science, it is not a stranger to people. People have been living in or near the olinguito’s cloud forest world for thousands of years. And, while misidentified, specimens have been in museums for more than 100 years, and at least one olinguito from Colombia was exhibited in several zoos in the United States during the 1960s and 1970s. There were even several occasions during the past century when the olinguito came close to being discovered but was not. In 1920, a zoologist in New York thought an olinguito museum specimen was so unusual that it might be a new species, but he never followed through in publishing the discovery.

Giving the olinguito its scientific name is just the beginning.

“This is the first step,” Helgen said. “Proving that a species exists and giving it a name is where everything starts. This is a beautiful animal, but we know so little about it. How many countries does it live in? What else can we learn about its behavior? What do we need to do to ensure its conservation?”

The team is already planning its next mission into the clouds.

LEARN MORE:

Participate in the Live Bilingual Google Hangout – Friday 8/16/2013

Read New Carnivore in Cloud Forest in the NC State Abstract Research Blog

Media Contacts:

D’Lyn Ford NC State Uuniversity

Emelia Cowans NC Museum of Natural Sciences